Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 24 July 2024 at 3:11AM.

51°31′05″N 0°05′19″W / 51.518188°N 0.088611°W / 51.518188; -0.088611

Moorfields was an open space, partly in the City of London, lying adjacent to – and outside – its northern wall, near the eponymous Moorgate. It was known for its marshy conditions, the result of the defensive wall acting as a dam, impeding the flow of the River Walbrook and its tributaries.[1]

Moorfields gives its name to the Moorfields Eye Hospital which occupied a site on the former fields from 1822–1899, and is still based close by, in the St Luke's area of the London Borough of Islington.[2]

Setting

Moorfields is first recorded in the late 12th century, though not by name, as a great fen. The fen was larger than the area subsequently known as Moorfields.

Moorfields was contiguous with Finsbury Fields, Bunhill Fields and other open spaces, and until its eventual loss in the 19th century, was the innermost part of a green wedge of land which stretched from the wall, to the open countryside which lay close by. Moorfields separated the western and eastern growth of London beyond the city wall – with the eastern extension being better known as the East End.

The fields were divided into four areas; the Little Moorfields, Moorfields proper, Middle Moorfields and Upper Moorfields.

Great Fen

The origins of Moorfields lie in a wider area, described by William Fitzstephen as the "great fen which washed against the northern wall of the City".[3] The marshy conditions appear to have been caused by London's Wall acting as a dam, restricting the flow of the river.[4]

The fen covered much of the Manor of Finsbury, but its exact extent is not clear. It has been suggested that it extended west from the Walbrook which fed it, extending to the vicinity of Old Street in the north, and the road from Cripplegate in the west. Other commentators have suggested that the topography of the area means the marsh probably didn’t extend as far west due to higher ground there, but did extend further north and possibly, in places, further east.[5]

Little Moorfields and Moorfields Proper

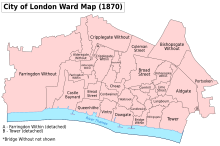

The Little Moorfields and Moorfields proper (also known as Lower Moorfields) were just north of London's wall, and from 1676 to 1815 included the Bethlem Hospital. Little Moorfields was the element that was left lying just west of Moorgate Street after a gap had been made in the wall to create the Moorgate, and the associated road from the north, in the 15th and 16th century. These parts were inside the City boundaries, lying in the Coleman Street Ward.

It is thought that this open space was not included within the City’s administrative boundaries until the 17th century, prior to that being part of the Manor of Finsbury.[6]

The Walbrook, known at this point as Deepditch and running on the line of modern Blomfield Street, seems to have formed the eastern boundary of Moorfields proper. It also formed an administrative boundary,[7] with Coleman Street Ward to the west (including the open spaces of Little Moorfields and Moorfields proper); while on the East End side lay the urbanised extra-mural ward of Bishopsgate Without, and also the parish of Shoreditch.

This section of the Walbrook, around Blomfield Street, was the focal point of the Walbrook Skulls; the result of the deposit of large numbers of decapitated Roman-era human skulls into the water.[8] These are still regularly uncovered during building work.

Middle and Upper Moorfields

Middle Moorfields and Upper Moorfields lay outside the City, to the north-west of Moorfields proper, in the Manor of Finsbury. The manor was coterminous with the parish of St Luke's (a late sub-division of the parish of St Giles-without-Cripplegate).[9]

Neighbouring areas

The Metropolitan Borough of Shoreditch (which replaced the parish of Shoreditch, being based on the same boundaries), had an electoral ward named Moorfields, this was adjacent to the former Moorfields (and also the famous Moorfields Eye Hospital) with only a small part of the area ever having been part of Moorfields, and only at an early date.

History

An early name for Moorfields proper appears to have been Moor Mead.[10] The Moor place-name element usually refers to fen environments,[11] and the wet nature of the area persisted, though this was improved by a drainage scheme in 1572.[12]

In the 15th century the monasteries of Charterhouse and St Bartholomews diverted the headwaters of the Walbrook to their sites in the River Fleet catchment. It has been suggested[13] that this caused a significant reduction in the flow of the river, causing Moorfields to become drier, and allowing the Mayor to construct the new Moorgate.

Moorgate was built by upgrading a postern built in 1415, and enlarged in 1472 and 1511. The gate remained poorly connected as there was no direct approach road from the south until 1846, long after the gate and wall were demolished.

After the Great Fire of London in 1666, refugees from the fire evacuated to Moorfields and set up temporary camps there. King Charles II of England encouraged the dispossessed to move on and leave London, but it is unknown how many newly impoverished and displaced persons instead settled in the Moorfields area.

In the early 18th century, Moorfields was the site of sporadic open-air markets, shows, and vendors/auctions. Additionally, the homes near and within Moorfields were places of the poor, and the area had a reputation for harbouring highwaymen, as well as brothels. James Dalton and Jack Sheppard both retreated to Moorfields when in hiding from the law. Parts of the area were known as public cruising areas for gay men.[14] A path in the Upper Moorfields, beside a wall that separated the Upper and Middle Moorfields, was known as Sodomites Walk: the wall was removed in 1752 but the path remains as the south side of Finsbury Square.[15]

In 1780 it was the site of some of the most violent rioting during the Gordon Riots.

The district was once the site of The Foundery, a former cannon foundry turned preaching house and an early centre of Wesleyan Methodism.[16]

A fashionable carpet manufactory was established here by Thomas Moore (c. 1700–1788) in the mid-eighteenth century. Moore's carpet manufactory at Moore Place made a number of fine carpets commissioned by the architect and interior designer, Robert Adam, for the grand rooms he designed for his wealthy clients. Thomas Moore lived at his home on Chiswell Street until his death. His Moore Park factory remained in operation until 1793, when his daughter, Jane, and her husband, Joseph Foskett, sold the lease to another carpet manufacturer.[17]

Demise and legacy

Much of Moorfields was developed in 1777, when Finsbury Square was developed; the remainder succumbed within the next few decades, notably when Moorfields proper was replaced by the modern Finsbury Circus in 1817.

Today the name survives in the names of Moorfields Eye Hospital (since moved to another site); St Mary Moorfields; Moorfields the short street (on which stands the headquarters of the British Red Cross) parallel with Moorgate (and containing some entrances to Moorgate station); and Moorfields Highwalk, one of the pedestrian "streets" at high level in the Barbican Estate. Moorfields Highwalk is featured in the music video to Robbie Williams' song "No Regrets".

References

- ^ On the wall eventually becoming an unintended? dam holding back the Walbrook https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/london/vol3/pp10-18

- ^ History from the hospital's own web page https://www.moorfields.nhs.uk/content/our-history

- ^ Recorded by William Fitzstephen, writing in the 1170s, a discussion on the extent of the marsh is included in "Reclaiming the Marsh" by Pre-Construct Archaeology. This was authored by Johnathon Butler and others and sub-titled “Archaeological excavations at Moor House, City of London

- ^ On the wall eventually becoming an inadvertent? dam to hold back the walbrook https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/london/vol3/pp10-18

- ^ Discussed in "Reclaiming the Marsh - Archaeological excavations at Moor House, City of London" by Pre-Construct Archaeology. The original suggestion had been made by Marjorie Honeybourne, with commentary and alternative views from the author of Chapter 5

- ^ The Ward did not extend beyond the wall at the time of John Stows survey of 1603 – but it did by the time of Ogilby and Morgans map of 1676

- ^ BHO source on the Moorfields area https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol8/pp88-90

- ^ London's Hadrianic War? Dominic Perring

- ^ Records of St Giles without Cripplegate, Chapter 6 see https://archive.org/stream/recordsstgilesc01dentgoog/recordsstgilesc01dentgoog_djvu.txt

- ^ Historical introduction: Moorfields. Vol. 8. London County Council, London. 2019 [1922]. pp. 88–90 – via British History Online.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Concise Oxford Dictionary of Place Names, Eilert Ekwall, fourth edition. He doesn't refer to Moorfields, only the place name element.

- ^ The London Encyclopaedia, Weinreb and Hibbert

- ^ Stephen Myers, The River Walbrook and Roman London, 2016

- ^ Norton, Rictor (1992). Mother Clap's Molly House: The Gay Subculture in England 1700–1830. London: Gay Men's Press. pp. 71–90. ISBN 0854491880.

- ^ Norton, Rictor, ed. (22 April 2000). "The Trial of William Brown, 1726". Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "List of publications published or distributed at the Foundry". Copac. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ^ "The Moores. » 28 Apr 1866 » The Spectator Archive". The Spectator Archive. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

9 Annotations

First Reading

Phil • Link

The above link is the rough location, as the fields stretched a good deal north and south. The northern end, Upper Moor Fields, can be seen on this map: http://www.motco.com/map/81002/Se…

Click 'South' to see the rest!

Pauline • Link

from L&M Companion

A large marshy area north of the city wall, built over in the 18th and early 19th centuries, and today covered by Finsbury Sq., Finsbury Circus and adjacent streets. Part of it was drained early in the 16th century, and by 1598 three windmills had been built. In 1605 the southern section was laid out by the city in pleasant walks, set with trees. It was much used for recreation.

Pedro • Link

Moorfields

The location of the Artillery Grounds of the Honourable Artillery Company, and a few brothels.

Pedro • Link

Moorfields and Finsbury

In Moorfields and about Finsbury, specimens of primitive skates have from time to time been exhumed, recalling the time when these were marshy fields, which in winter were resorted to by the youth of London for the amusements which Fitzstephen describes. A pair preserved in the British Museum.

(Book of Days)

MOORFIELDS AND FINSBURY History...

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/…

Rex Gordon • Link

Stow's Survey on Moorfields (The Suburbs Without the Walls), about 1598:

This field of old time was called the More, as appeareth by the charter of William the Conqueror to the college of St. Martin, declaring a running water to pass into the city from the same More. Also Fitzstephen writeth of this More, saying thus: "When the great fen, or moor, which watereth the walls on the north side, is frozen," etc. This fen, or moor field, stretching from the wall of the city betwixt Bishopsgate and the postern called Cripples gate, to Fensbery and to Holy well, continued a waste and unprofitable ground a long time, so that the same was all letten for four marks the year, in the reign of Edward II; but in the year 1415, the 3rd of Henry V, Thomas Fawconer, mayor ... caused the wall of the city to be broken toward the said moor, and built the postern called Moregate, for the ease of the citizens to walk that way upon causeys towards Iseldon and Hoxton ... In the year 1498 all the gardens, which had continued time out of mind without Moregate, to wit, about and beyond the lordship of Finsbury, were destroyed; and of them was made a plan field for archers to shoot in. And in the year 1512, Roger Archley, mayor, caused divers dikes to be cast, and made to drain the waters of the said Morefielde, with bridges arched over them, and the grounds about to be levelled, whereby the said field was made somewhat more commodious, but yet it stood full of noisome waters; whereupon, in the year 1527, Sir Thomas Semor, mayor, caused divers sluices to be made to convey the said waters over the Town ditch, into the course of the Walbrooke, and so into the Thames; and by these degrees was this fen or moor at length made main and hard ground, which before being overgrown with flags, sedges, and rushes, served no use; since which time also the further grounds beyond Finsbury court have been so overheightened with lay-stalls of dung, that now three windmills are thereon set; the ditches be filled up, and the bridges overwhelmed.

Second Reading

Bill • Link

Moorfields, a moor or fen without the walls of the City to the north, first drained in 1527; laid out into walks for the first time in 1606, and first built upon late in the reign of Charles II. The name has been swallowed up in Finsbury (or Fensbury) Square, Finsbury Circus, the City Road, and the adjoining localities.

This low-lying district became famous for its musters and pleasant walks; for its laundresses and bleachers; for its cudgel players and popular amusements; for its madhouse, better known as Bethlehem Hospital; and for its bookstalls and ballad-sellers.

In a petition of the Lord Mayor and Corporation of London to the King, James I., about 1625, they state that they have at great charge made pleasant walks out of the boggy fields north of London, and pray his Majesty will direct the construction of a new street to lead to the said walks.

After the Great Fire of London in 1666 the people lived in sheds and tents in Moorfields till such time as other tenements could be erected for them.

---London, Past and Present. H.B. Wheatley, 1891.

Bill • Link

There is an encyclopedia entry for Moorgate: http://www.pepysdiary.com/encyclo…

Bill • Link

Moorfields were first drained in 1527, and walks were laid out in 1606. In the following year Richard Johnson wrote "The Pleasant Walks of Moore fields."

---Wheatley, 1899.

Third Reading

San Diego Sarah • Link

The oldest known map of London is Copperplate and very detailed -- it dates from the reign of Queen Mary (the Bloody) -- and shows Moor Fields. The caption says:

"Moor Fields: One of the standout locations on the map shows numerous women laying out clothing to dry in the Moor Fields. In one case, a length of cloth has been drawn out and pinned to the ground, a technique known as tentering. Spitalfields, to the top right of the map, still contains a street called Tenter Ground to this day, recalling the practice so beautifully sketched on the Copperplate map. The lower half of the map includes three further areas where long strips of cloth are drawn out along a series of posts.

"The Moor Fields were often waterlogged — partly because the city wall impeded the flow of the Walbrook stream hereabouts. I’d never noticed until colouring in the map just how many water channels are depicted in this area (I’ve shown them in a grey-blue). We can distinguish these rivulets from other boundaries thanks to a number of small bridges that cross over them."

To see the map in the original black-and-white, and the new colorized version, see

https://londonist.substack.com/p/…