Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 22 July 2024 at 6:10AM.

| Hungerford | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

| |

Town symbol | |

Location within Berkshire | |

| Area | 27.52 km2 (10.63 sq mi) |

| Population | 5,869 (2021 Census)[1] |

| • Density | 213/km2 (550/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | SU334681 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | HUNGERFORD |

| Postcode district | RG17 |

| Dialling code | 01488 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Royal Berkshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Town Council |

Hungerford is a historic market town and civil parish in Berkshire, England, 8 miles (13 km) west of Newbury, 9 miles (14 km) east of Marlborough, 27 miles (43 km) north-east of Salisbury and 60 miles (97 km) west of London. The Kennet and Avon Canal passes through the town alongside the River Dun, a major tributary of the River Kennet. The confluence with the Kennet is to the north of the centre whence canal and river both continue east. Amenities include schools, shops, cafés, restaurants, and facilities for the main national sports. Hungerford railway station is a minor stop on the Reading to Taunton Line.

History

Hungerford is derived from an Anglo-Saxon name meaning "ford leading to poor land".[2] The town's symbol is the estoile and crescent moon.[3] The place is not described in the Domesday Book of 1086 because four ancient manors each owned some property within Hungerford, a possession located at the extreme western edge of the royal manor of Kintbury,[4] in the ancient hundred of Kintbury.[5] The manor of Standen Hussey, described as Standen in Wiltshire in Domesday,[6] was later in Hungerford parish.[7] The land was granted to Robert de Beaumont, 1st Earl of Leicester. When he died in 1118, he passed his English estates, including Hungerford, to his son Robert and his heirs who encouraged the town's growth over the next 70 years.[4]

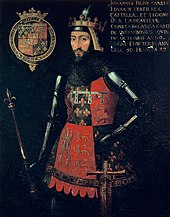

By 1241, Hungerford called itself a borough.[8] In the late 14th century, John of Gaunt was lord of the manor and he granted the people the lucrative fishing rights on the River Kennet.[9] The family of Walter Hungerford, 1st Baron Hungerford originated in the town (c. 1450), although after three generations the title passed to Baroness Hungerford who married Sir Edward Hastings who became a Baron,[10] and the family seat moved to Heytesbury, Wiltshire.[11] In the 16th century, the parish of Hungerford was included in the formation of the hundred of Kintbury Eagle.[12]

During the Civil War, the Earl of Essex and his army spent the night here in June 1644. In October of the same year, the Earl of Manchester’s cavalry were quartered in the town. Then, in the November, Charles I’s forces arrived in Hungerford on their way to Abingdon.[13] During the Glorious Revolution of 1688, William of Orange was offered the Crown of England while staying at the Bear Inn in Hungerford.[14] The Hungerford land south of the river Kennet was for centuries, until a widespread growth in cultivation in the area in the 18th century, in Savernake Forest.[15]

1987 Massacre

The Hungerford massacre occurred on 19 August 1987. A 27-year-old unemployed local labourer, Michael Robert Ryan, armed with three weapons, a Type 56 assault rifle, a Beretta pistol and an M1 carbine, shot and killed 16 people in and around the town – including his mother – and wounded 15 others, then killed himself in a local school after being surrounded by armed police. All his victims were shot in the town or in nearby Savernake Forest.[16]

Home Secretary Douglas Hurd commissioned a report on the massacre from the Chief Constable of Thames Valley Police, Colin Smith. The massacre was one of three significant firearms atrocities in the United Kingdom after the invention of rapid fire weapons such as the one involved, the other two being the Dunblane massacre and the Cumbria shootings. It led to the passing of the Firearms (Amendment) Act 1988, which banned the ownership of semi-automatic centre-fire rifles, and restricted the use of shotguns with a magazine capacity of more than two rounds. The Hungerford Report confirmed that Ryan's collection of weapons was legally licensed.[17]

Government

Hungerford is a civil parish, covering the town of Hungerford and a surrounding rural area, including the small village of Hungerford Newtown. The parish was divided into four tithings: Hungerford or Town, Sanden Fee, Eddington with Hidden and Newtown and Charnham Street. North and South Standen and Charnham Street were officially detached parts of Wiltshire until transferred to Berkshire in 1895. Leverton and Calcot were transferred to Hungerford parish from Chilton Foliat in Wiltshire in 1895. The parish shares boundaries with the Berkshire parishes of Lambourn, East Garston, Great Shefford, Kintbury and Inkpen, and with the Wiltshire parishes of Shalbourne, Froxfield, Ramsbury and Chilton Foliat.[18] Parish council responsibilities are undertaken by Hungerford Town Council, which consists of fifteen volunteer councillors and committee members, supported by a full-time clerk. The mayor is elected from amongst their numbers.

The parish forms part of the district administered by the unitary authority of West Berkshire, and local government responsibilities are shared between the town council and unitary authority. Hungerford is part of the Newbury parliamentary constituency. Hungerford participates in town twinning to foster good international relations:

Geography

Hungerford is on the River Dun. It is the westernmost town in Berkshire, on the border with Wiltshire. It is in the North Wessex Downs. The highest point in the entire South East England region is the 297 m (974 ft) summit of Walbury Hill, 4 mi (6.4 km) from the town centre. The Kennet and Avon Canal separates Hungerford from what might be described as the town's only suburb, the hamlet of Eddington. The town has, as its western border, a county divide which also marks the border of the South East and South West England regions; it is 60 mi (97 km) west of London and 55 mi (89 km) east of Bristol on the A4. It is almost equidistant from the towns of Newbury and Marlborough. Freeman's Marsh, on the western edge of the town, is a Site of Special Scientific Interest.[20]

Transport

Hungerford is situated on several transport routes, including the M4 motorway with access at Junction 14, the Old Bath Road (A4), and the Kennet and Avon Canal, the latter opened in 1811. Hungerford railway station is on the Reading to Taunton line; a reasonable rail service to Newbury, Reading and Paddington means that Hungerford has developed into something of a dormitory town which has been slowly expanding since the 1980s. Many residents commute to nearby towns such as Newbury, Swindon, Marlborough, Thatcham and Reading.

Church

The parish church of St. Lawrence stands next to the Kennet and Avon Canal. It was rebuilt in 1814–1816 by John Pinch the elder in the Gothic Revival style.[21] The east window contains stained glass by Lavers and Westlake. The church is a Grade II* listed building.[22]

Sport and leisure

Hungerford has a cricket team,[23] a football team, Hungerford Town F.C., that plays at the Bulpit Lane ground, a rugby team, Hungerford RFC.[24] and a netball club. Hungerford Archers, an archery club, uses the sports field of the John O'Gaunt School as its shooting ground.[23] Hungerford Hares Running Club was established in 2007.[25]

Hocktide

Hungerford is the only place in the country to have continuously celebrated Hocktide or Tutti Day (the second Tuesday after Easter). Today it marks the end of the town council's financial and administrative year, but in the past it was a more general celebration associated with the town's great patron, John of Gaunt. Its origins are thought to lie in celebrations following King Alfred's expulsion of the Vikings. The "Bellman" (or town crier) summons the Commoners of the town to the Hocktide Court held at Hungerford Town Hall, while two florally decorated "Tutti Men" and the "Orange Man" visit every house with commoners' rights (almost a hundred properties), accompanied by six Tutti Girls, drawn from the local school. Originally they collected "head pennies" to ensure fishing and grazing rights. Today, they largely collect kisses from each lady of the house. In the court, the town's officers are elected for the coming year and the accounts examined. The court manages the town hall, the John of Gaunt Inn, the Common, Freeman's Marsh, and fishing rights in the River Kennet and river Dun.

Legends

There is an old legend that "Hingwar the Dane", better known as Ivarr the Boneless, was drowned accidentally while crossing the Kennet here, and that the town was named after him. This stems from the, probably mistaken, belief that the Battle of Ethandun took place at Eddington in Berkshire rather than Edington, Wiltshire, or Edington, Somerset.

Literature

Hungerford is one of two places which arguably meet the criteria for Kennetbridge in Thomas Hardy's novel Jude the Obscure, being "a thriving town not more than a dozen miles south of Marygreen"[26] (Fawley) and is between Melchester (Salisbury) and Christminster (Oxford).[27] The main road (A338) from Oxford to Salisbury runs through Hungerford. The other contender is the larger town of Newbury.

Notable people

- Charlie Austin, footballer

- Adam Brown, actor, comedian and pantomime performer

- Samuel Chandler, Nonconformist theologian and preacher

- Christopher Derrick, author

- Edward Duke (1779–1852), antiquary

- Ralph Evans (1915–1996), footballer

- John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, son of King Edward III

- William Greatrakes, connected with the authorship of the Letters of Junius

- Nicholas Monro (b. 1936), artist, had a studio at Hungerford[28]

- George Pocock (1774–1843), the founder of the Tent Methodist Society and inventor of the Charvolant

- Charles Portal, 1st Viscount Portal of Hungerford, Chief of the Air Staff during most of World War II and Marshal of the Royal Air Force

- Reginald Portal, admiral

- Henry "Harry" Quelch (1858–1913), one of the first British Marxists

- Edmund Roche, 5th Baron Fermoy, maternal uncle of Diana, Princess of Wales, died in Hungerford in 1984

- Robert Snooks, last highwayman to be hanged in England, born in Hungerford in 1761

- James E. Talmage, (1862–1933) LDS Church leader, writer and theologian. Author of Jesus the Christ

- Jethro Tull (agriculturist), died in the town

- Will Young, singer

Demography

| Output area | Homes owned outright | Owned with a loan | Socially rented | Privately rented | Other | km2 roads | km2 water | km2 domestic gardens | Usual residents | km2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Civil parish | 834 | 858 | 367 | 482 | 43 | 0.500 | 0.337 | 0.789 | 5767 | 27.52 |

Freedom of the Town

The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the Town of Hungerford.

Individuals

- Jennifer Bartter: 3 September 2022.[30]

- Martin Crane: 3 September 2022.[30]

- Penny Locke: 3 September 2022.[30]

See also

References

- ^ "Hungerford". City population. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Mills, A.D. (1991). Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-869156-4.

- ^ "Crescent and Star". Hungerford Virtual Museum. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ a b Manorial History. Hungerford Virtual Museum. Accessed 5 April 2023.

- ^ Open Domesday: Hundred of Kintbury. Accessed 5 April 2023.

- ^ Open Domesday: Standen (Land of Arnulf of Hesdin). Accessed 5 April 2023.

- ^ Kinwardstone Hundred. British History Online. Accessed 5 April 2023.

- ^ Page, William; Ditchfield, P. H. (1924). "'Parishes: Hungerford', in A History of the County of Berkshire". London: British History Online. pp. 183–200. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Live Like Common People". The Telegraph. 22 December 2004. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Nicolas, Nicholas Harris (1826). Testamenta Vetusta. Vol. II. London: Nicholas and Son. pp. 372, 431.

- ^ "Heytesbury". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Kintbury Eagle hundred. British History Online. Accessed 5 April 2023.

- ^ "1642-51 Civil War". Hungerford Virtual Museum. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "The Battle of Broad Street". Berkshire History. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "A Brief History of Hungerford Park". Penny Post. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 169

- ^ The Hungerford Report – Shooting Incidents At Hungerford On 19 August 1987, Chief Constable of Thames Valley Police Colin Smith to Home Secretary Douglas Hurd. Retrieved 24 August 2007. Archived 22 January 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Election Maps". Ordnance Survey. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ^ "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Magic Map Application". Magic.defra.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ "Statement of Significance: Hungerford St Lawrence" (PDF). 1 May 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Historic England (6 February 1962). "Church of St. Lawrence (Grade II*) (1289541)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ a b Hungerford in West Berkshire – Sports. Hungerford.uk.net. Retrieved on 17 July 2013.

- ^ Boulton, Bob. (29 April 2013) Hungerford RFC. Pitchero.com. Retrieved on 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Hungerford Hares". Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Thomas Hardy. "Paragraph 4, Chapter VII, Part Fifth, Jude the Obscure".

- ^ Thomas Hardy. "Paragraph 6, Chapter X, Part Third, Jude the Obscure".

- ^ Radio Birmingham interview with Munro, 11 May 1972, transcribed in part in Towers, Alan (July–August 1972). "Birmingham: Nicholas Munro". Studio International. 184 (946): 18.

- ^ Key Statistics: Dwellings; Quick Statistics: Population Density; Physical Environment: Land Use Survey 2005

- ^ a b c Garvey, John (3 September 2022). "Revealed: This year's winners of the Freedom of the Town of Hungerford awards". The Newbury Weekly News. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

External links

3 Annotations

Second Reading

Terry Foreman • Link

Hungerford is a historic market town and civil parish in Berkshire, England, centred 8 miles (13 km) west of Newbury, 9 miles (14 km) east of Marlborough, 30 miles (48 km) northeast of Salisbury and 67 miles (107 km) west of London. Hungerford is a slight abbreviation and vowel shift from a Saxon name meaning 'Hanging Wood Ford'. The town’s symbol is the six-pointed star and crescent moon. The place does not occur in the Domesday Book of 1086, but certainly existed by 1173. By 1241, it called itself a borough. In the late 14th century, John of Gaunt was medieval lord of the manor and he granted the people the lucrative fishing rights on the River Kennet. During the English Civil War, the Earl of Essex and his army spent the night here in June 1644. In October of the same year, the Earl of Manchester’s cavalry were also quartered in the town. Then, in the November, the King’s forces arrived in Hungerford on their way to Abingdon. During the Glorious Revolution of 1688, William of Orange was offered the Crown of England while staying at the Bear Inn in Hungerford. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hun…

San Diego Sarah • Link

Because Hungerford is on the London-to-Bristol and the London-to-Bath routes, famous people requently visited the town.

Royal visitors are traditionally presented with a Lancastrian red rose outside the Bear Inn. One of the monarch's titles is the Duke of Lancaster.

In the 13th century the town was known as Hungerford Regis when it passed from the King to the Dukes of Lancaster.

John of Gaunt, a 14th century Duke of Lancaster, gave the townsfolk the rare privilege to fish in the River Kennet. They received his horn and a charter affirming his gift, but the latter was stolen during the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

The Duchy of Lancaster then tried to re-establish its rights over the Kennet and a court case ensued which was only resolved when Queen Elizabeth intervened on behalf of the town.

The Bear Inn, Charnham Street was a hospice as early as 1464. It may have been connected with the Hospital of St. John, established in the area by Henry III.

During the Civil Wars, Hungerford was often a stopover.

In 1643, before the First Battle of Newbury, Parliamentarian soldiers were stationed there having clashed with Prince Rupert at Aldbourne Chase, and several died of their wounds. Their burials are recorded in the parish register.

Troops of Robert Devereaux, 3rd Earl of Essex and Edward Montagu, Earl of Manchester were in town before the Second Battle of Newbury in 1644.

After the retreat from the Second Battle of Newbury, King Charles used the Bear as his headquarters. He stayed for 3 days with about 1,000 troops in the neighborhood.

He was going to Basing House, Hants., but news arrived that his help was not needed, so he marched to Faringdon.

The Hampshire Militia was stationed in Hungerford before they joined Cromwell after the Second Battle of Worcester.

In August 1663, Charles II and Queen Catherine passed through Hungerford on their way to Bath.

James, Duke of York passed stayed at nearby Littlecote Hall in 1663.

On 26 September, 1665, Charles II rode through Hungerford, four men having been instructed by the Constable 'to dig ye high waies' in preparation for the King's arrival, each man being paid 3d for his services.

San Diego Sarah • Link

MORE

A unique room at Littlecote Hall is the "Dutch Parlour". A plaque in the corridor says it was decorated with paintings by Dutch seamen who were captured in the second Anglo-Dutch war; these paintings cover the walls and the ceiling. (Some are quite risque.)

The Hall was owned by the Popham family, who played a role in the history of deaf education when John Wallis and William Holder taught Alexander Popham (born 1648) be able to speak.

Queen Catherine again rode through Hungerford in 1677 on her way to Bath.

Queen Mary of Modena passed through Hungerford twice in 1687, on her way to and from Bath.

In December 1688, William of Orange stayed at Littlecote Hall, on his march from Brixham to London. The Bear Inn was the site of his meetings with James II's commissioners. They wanted to know his intensions, and preferably to secure his retreat, but were quietly told it would be best if James left.

A photo of the Bear:

http://www.berkshirehistory.com/v…

Littlecote Hall photos: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lit…

More about Hungerford: https://www.hungerfordvirtualmuse…