Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 27 July 2024 at 3:10AM.

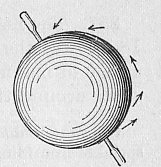

A terrella (Latin for 'little earth') is a small magnetised model ball representing the Earth, that is thought to have been invented by the English physician William Gilbert while investigating magnetism, and further developed 300 years later by the Norwegian scientist and explorer Kristian Birkeland, while investigating the aurora.

Terrellas have been used until the late 20th century to attempt to simulate the Earth's magnetosphere, but have now been replaced by computer simulations.

William Gilbert's terrella

William Gilbert, the royal physician to Queen Elizabeth I, devoted much of his time, energy and resources to the study of the Earth's magnetism. It had been known for centuries that a freely suspended compass needle pointed north. Earlier investigators (including Christopher Columbus) found that direction deviated somewhat from true north, and Robert Norman showed the force on the needle was not horizontal but slanted into the Earth.

William Gilbert's explanation was that the Earth itself was a giant magnet, and he demonstrated this by creating a scale model of the magnetic Earth, a "terrella", a sphere formed out of a lodestone. Passing a small compass over the terrella, Gilbert demonstrated that a horizontal compass would point towards the magnetic pole, while a dip needle, balanced on a horizontal axis perpendicular to the magnetic one, indicated the proper "magnetic inclination" between the magnetic force and the horizontal direction. Gilbert later reported his findings in De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure, published in 1600.

Kristian Birkeland's terrella

Kristian Birkeland was a Norwegian physicist who, around 1895, tried to explain why the lights of the polar aurora appeared only in regions centered at the magnetic poles.

He simulated the effect by directing cathode rays (later identified as electrons) at a terrella in a vacuum tank, and found they indeed produced a glow in regions around the poles of the terrella. Because of residual gas in the chamber, the glow also outlined the path of the particles. Neither he nor his associate Carl Størmer (who calculated such paths) could understand why the actual aurora avoided the area directly above the poles themselves. Birkeland believed the electrons came from the Sun, since large auroral outbursts were associated with sunspot activity.

Birkeland constructed several terrellas. One large terrella experiment was reconstructed in Tromsø, Norway.[2]

Other terrellas

The German Baron Carl Reichenbach (1788–1869) also experimented with a terrella. He used an electromagnet, placed within a large hollow iron sphere, and this was examined in the darkroom under varying degrees of electrification.

Brunberg and Dattner in Sweden, around 1950, used a terrella to simulate trajectories of particles in the Earth's field. Podgorny in the Soviet Union, around 1972, built terrellas at which a flow of plasma was directed, simulating the solar wind. Hafiz-Ur Rahman at the University of California, Riverside conducted more realistic experiments around 1990. All such experiments are difficult to interpret, and are never able to scale all the parameters needed to properly simulate the Earth's magnetosphere, which is why such experiments have now been completely replaced by computer simulations.

Recently the terrella experiments have been further developed by a team of physicists at the Institute of Planetology and Astrophysics in Grenoble, France to create the "planeterrella" which uses two magnetised spheres which can be manipulated to recreate several different auroral phenomena.[3]

Notes

- ^ Section 2, Chapter VI, p. 678

References

- ^ a b Birkeland, Kristian (1908–1913). The Norwegian Aurora Polaris Expedition 1902-1903. New York and Christiania (now Oslo): H. Aschehoug & Co – via archive.org. out-of-print, full text online

- ^ Terje Brundtland. "The Birkeland Terrella". Sphæra (7). Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Planeteterrella - English".

9 Annotations

First Reading

TerryF • Link

Terrella in the Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terr…

William Gilbert’s ‘Terrella’

http://www.acmi.net.au/AIC/TERREL…

William Gilbert (or Gilberd, as he wrote it…)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Will…

William Gilbert aka William of Colchester "set out to debunk magical notions of magnetism, yet in building an intellectual bridge between natural philosophy and emerging sciences, he did not completely abandon reference to the occult. For example, he believed that an invisible ‘orb of virtue’ [force] surrounds a magnet and extends in all directions around it. Other magnets and pieces of iron react to this orb of virtue and move or rotate in response. Magnets within the orb are attracted whereas those outside are unaffected. The source of the orb remained a mystery. Although his language was that of the natural philosophy of the time, some of his ideas were ahead of his time. His orbs of virtue were a fledgling notion of the idea of fields that would revolutionize physics more than two centuries later."

http://chem.ch.huji.ac.il/~eugeni…

TerryF • Link

*De Magnete*

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_M…

‘De Magnete’ page 155

http://www.new-science-theory.com…

Halley and the ‘Paramour’[and *De Magnete* p. 192]

http://www.nmm.ac.uk/server/show/…

TerryF • Link

De Magnete by William Gilbert [English trans. excerpts ]

[ concerning loadstones and their magnetic properties ] http://campus.udayton.edu/~hume/G…

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Load…

in aqua • Link

Exposure to Sam on his first visit to this august group, but mentioned by John Evelyn.Wednesday 23 January 1660/61

"With [Greatorex] to Gresham Colledge (where I never was before), and saw the manner of the house, and found great company of persons of honour there"

http://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1…

:[jan 1661 J Evelyn ]23. To Lond, at our Society, where was divers Exp: on the Terrella sent us by his Majestie

RennyBA • Link

I think you have an very interesting article of the phenomena Terrella her and as a Norwegian of course I know about Birkeland's Terella.

I'm a blogger and write about Norway, our cultures, traditions and habits and call it my Terella. My little earth or the world seen trough my eyes if you like.

Terry Foreman • Link

Two terrellae

A terrella (‘little earth’) is a sphere made of a magnetized substance, used to simulate the magnetic field of the earth. In the 16th century the English physician William Gilbert used a terrella made out of lodestone (a naturally-occurring magnetized mineral) to demonstrate that the earth is magnetic, and to explain how mariners’ compasses work. The Society used several terrellae in experimental demonstrations at meetings in the 17th century. Sir Christopher Wren donated one that was the same size as the larger of these two examples (bottom image). http://royalsociety.org/exhibitio…

Second Reading

Bill • Link

Professor Silvanus P. Thompson, F.R.S., has kindly supplied me with the following interesting note on the terrella (or terella):

The name given by Dr. William Gilbert, author of the famous treatise, " De Magnete" (Lond. 1600), to a spherical loadstone, on account of its acting as a model, magnetically, of the earth; compass-needles pointing to its poles, as mariners' compasses do to the poles of the earth.

The term was adopted by other writers who followed Gilbert, as the following passage from Wm. Barlowe's " Magneticall Aduertisements" (Lond. 1616) shows: "Wherefore the round Loadstone is significantly termed by Doct. Gilbert Terrella, that is, a little, or rather a very little Earth: For it representeth in an exceeding small model (as it were) the admiral properties magneticall of the huge Globe of the earth" {op. cit., p. 55).

Gilbert set great store by his invention of the terrella, since it led him to propound the true theory of the mariners' compass. In his portrait of himself which he had painted for the University of Oxford he was represented as holding in his hand a globe inscribed terella. In the Galileo Museum in Florence there is a terrella twenty-seven inches in diamater, of loadstone from Elba, constructed for Cosmo de' Medici. A smaller one contrived by Sir Christopher Wren was long preserved in the museum of the Royal Society (Grew's "Rarities belonging to the Royal Society," p. 364). Evelyn was shown "a pretty terrella described with all ye circles and shewing all ye magnetic deviations" (Diary, July 3rd, 1655).

---Wheatley, 1893.

Most portraits of Gilbert on the interwebz crop out the terrella. This one doesn’t: https://www.plasma-universe.com/F…

Bill • Link

...but more interesting to us is his [Christopher Wren's] arrangement of a huge terrella in an opening in a flat board "till it be like a globe with the poles in the horizon." This board he dusted over with steel filings "equally from a sieve" and then studied the curves of the filings as they delineated the magnetic spectrum. Sprat tells us that he found that "the lines of the directive virtue of the lodestone" are "oval" and that appears to have been another recognition of "lines" of directive virtue—a conception curiously similar to Faraday's lines of magnetic force.

---A History of Electricity. P. Benjamin, 1895.

San Diego Sarah • Link

Lodestones are lumpy and slate-gray, but their “magnetic intelligence” made them fabulously expensive in the Early Modern era.

Author and scientist William Gilbert thought that magnets had souls. At least, that was the accepted explanation for magnetism circa 1600, as explained in his influential De Magnete. Gilbert experimented with lodestones, lumps of magnetite that, after being struck by lightning, turn into natural magnets.

As he watched the lodestone pull the iron to it (or the iron leaping to the lodestone), Gilbert imagined them possessed of a magnetic intelligence that drew them together, like lovers. "Our planet is no mute lump of rock, but an animate creature, turning over in space like a sunbather who wants to get tan on both sides," he wrote.

William Gilbert was no crackpot. He was the first to propose the existence of the Earth’s magnetic field. For him that meant the Earth was imbued with a living soul.

William Gilbert was a Copernican, and he attributed the Earth’s rotation to its magnetic intelligence: “Were not the earth to revolve with diurnal rotation, the sun … would scorch the earth, reduce it to powder, and dissipate its substance … In other parts all would be horror, and all things frozen stiff with intense cold: hence all its eminences would be hard, barren, inaccessible, sunk in everlasting shadow and unending night. And as the earth herself cannot endure so pitiable and so horrid a state of things on either side, with her astral magnetic mind she moves in a circle … So the earth seeks and seeks the sun again, turns from him, follows him, by her wondrous magnetical energy.”

His book, De Magnete, ushered in a burst of magnetic enthusiasm. Lodestones ranked among porphyry and jasper as precious stones in this era of obsession with the wonders of the natural world. No alchemists' laboratory was complete without one — in part because they were fabulously expensive.

The price commanded by a powerful magnet meant that sailors, who really needed them for their compasses, had to make do with weaker lodestones.

Lodestones were also thought to have healing powers. Gout sufferers wore magnetic rings; poultices of pulverized lodestone were used to draw out bullets and arrowheads, and Queen Anne used a lodestone to heal sufferers of the King’s Evil (she was too squeamish to lay her hands directly on her scrofulous subjects).

More from https://daily.jstor.org/the-souls…