Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 26 July 2024 at 5:10AM.

51°22′01″N 1°36′00″E / 51.367°N 1.600°E / 51.367; 1.600

| St James' Day Battle | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Anglo-Dutch War | |||||||

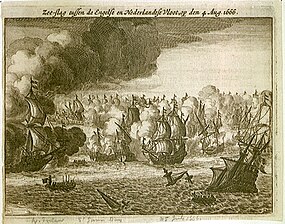

Engraving showing the St. James Day battle August 4th, 1666, between English and Dutch ships | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

England England |

Dutch Republic Dutch Republic | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Michiel de Ruyter | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| |||||||

The St James' Day Battle[a] took place on 25 July 1666 [b] (4 August 1666 in the Gregorian calendar), during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. It was fought between an English fleet commanded jointly by Prince Rupert of the Rhine and George Monck, and a Dutch force under Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter.

Although a clear English victory, this ultimately proved to be of limited strategic value.

Background

After the Dutch had inflicted enormous damage on the English fleet in the Four Days Battle of 1–4 June 1666 which is normally considered a Dutch victory,[3] the Dutch leading politician grand pensionary Johan de Witt ordered Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter to carry out a plan that had been prepared for over a year: to land in the Medway to destroy the English fleet while it was being repaired in the Chatham dockyards. For this purpose ten fluyt ships carried 2,700 marines of the newly created Dutch Marine Corps, the first in history. Also De Ruyter was to combine his fleet with the French one.

The French however did not show up and bad weather prevented the landing. De Ruyter had to limit his actions to a blockade of the Thames. On the 1st of August he observed that the English fleet was leaving port - earlier than expected. Then a storm drove the Dutch fleet back to the Flemish coast. On the 3rd De Ruyter again crossed the North Sea, leaving behind the troop ships.

Battle

First day

In the early morning of 25 July, the Dutch fleet of 88 ships discovered the English fleet of 89 ships near North Foreland, sailing to the north. De Ruyter gave orders for a chase and the Dutch fleet pursued the English from the southeast in a leeward position, as the wind blew from the northwest. Suddenly, the wind turned to the northeast. The English commander, Prince Rupert of the Rhine, then turned sharply east to regain the weather gauge. De Ruyter followed, but the wind fell and the fleet fell behind. The Dutch van, commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Johan Evertsen, was becalmed and drifted away from the line of battle, splitting De Ruyter's fleet in two. This awkward situation lasted for hours; then, again, a soft breeze began to blow from the northeast. Immediately, the English van, commanded by Thomas Allin, and part of the centre formed a line of battle and engaged the Dutch van, still in disarray.

The Dutch failed to form a coherent line of battle in response, and ship after ship was mauled by the combined firepower of the English line. Vice-Admiral Rudolf Coenders was killed, and Lieutenant-Admiral Tjerk Hiddes de Vries had an arm and a leg shot off, yet still tried to bring cohesion to his force — but to no avail. Unable to reach them with his centre, the horrified De Ruyter saw the Frisian ships drifting to the south, now no more than floating wrecks full of dead, the moans of the dying clearly audible above the other sounds of battle.

With the Dutch van defeated, the English converged to deliver the coup-de-grâce to De Ruyter's centre. George Monck, accompanying Rupert, predicted that De Ruyter would give two broadsides and run, but the latter put up a furious fight on the Dutch flagship De Zeven Provinciën. He withstood a combined attack by Sovereign of the Seas and Royal Charles and forced Rupert to leave the damaged Royal Charles for Royal James. The Dutch centre's resistance enabled the seaworthy remnants of the van to make an escape to the south.

Lieutenant-Admiral Cornelis Tromp, commanding the Dutch rear, had from a great distance seen the disaster for the Dutch fleet evolve. Annoyed by what he saw as a lack of competence, he decided to give the correct example. He turned sharply to the west, crossed the line of the British rear, under the command of Jeremiah Smith, separating it from the rest of the English fleet and then, having the weather gauge, kept on attacking it rabidly until at last the British were routed and fled to the west. He pursued well into the night, destroying HMS Resolution with a fireship. After Tromp three times shot the entire crew from its rigging, Smith's flagship HMS Loyal London caught fire and had to be towed home. The vice commander of the English rear was Edward Spragge, who felt so humiliated by the course of events that he became a personal enemy of Tromp. He would later be killed pursuing Tromp in the Battle of the Texel.[4]

Second day

On the morning of 26 July, Tromp broke off pursuit, well-pleased with his first real victory as a squadron commander. During the night, a ship had brought him the message that De Ruyter had likewise been victorious, so Tromp was in a euphoric mood. That abruptly changed upon the discovery of the drifting flagship of the dying Tjerk Hiddes de Vries. Suddenly he feared that his ship was now the only remnant of the Dutch fleet and that he was in mortal peril. Behind him, those ships of the English rear still operational had again turned to the east. In front, the other enemy squadrons surely awaited him. On the horizon, only English flags were to be seen. Manoeuvring wildly, Tromp, drinking a lot of gin to restore his nerve, dodged any attempt to trap him and brought his squadron safely home in the port of Flushing on the morning of 26 July. There, to great mutual relief, he discovered the rest of the Dutch fleet.

It took Tromp six hours to gather enough courage to face De Ruyter. It was obvious to him that he should never have allowed himself to get completely separated from the main force. Indeed, De Ruyter, not being his usual charitable self, immediately blamed him for the defeat and ordered Tromp and his subcommanders Isaac Sweers and Willem van der Zaan from his sight, and told them to never again set foot on De Zeven Provinciën. The commander of the Dutch fleet still had not mentally recovered from the events of the previous day.

On the morning of 5 August, after a short summer's night, De Ruyter discovered that his position had become hopeless. Lieutenant-Admiral Johan Evertsen had died after losing a leg, De Ruyter's force was now reduced to about forty ships, crowding together and most of these were inoperational, being survivors of the van. Some fifteen good ships had apparently deserted during the night. A strong gale from the east prevented an easy retreat to the continental coast, and to the west the British van and centre (about fifty ships) surrounded him in a half-circle, safely bombarding him from a leeward position.

De Ruyter was desperate. When his second-in-command of the centre, Lieutenant-Admiral Aert Jansse van Nes visited him for a council of war, he exclaimed: "With seven or eight against the mass!" He then sagged, mumbling: "What's wrong with us? I wish I were dead." His close personal friend Van Nes tried to cheer him up, joking: "Me too. But you never die when you want to!" No sooner had both men left the cabin than the table they had been sitting at was smashed by a cannonball.

The English, however, had their own problems. The strong gale prevented them from closing with the Dutch. They tried to use fire ships, but these, too, had trouble reaching the enemy. Only the sloop Fan-Fan, Rupert's personal pleasure yacht, rowed to the Dutch flagship De Zeven Provinciën to harass it with its two little guns, much to the hilarious laughter of the English crews.

When his ship had again warded off an attack by a fireship (the Land of Promise) and Tromp still did not show up, for De Ruyter tension became unbearable. He sought death, exposing himself deliberately on the deck. When he failed to be hit, he exclaimed: "Oh, God, how unfortunate I am! Amongst so many thousands of cannonballs, is there not one that would take me?" His son-in-law, Captain of the Marines Johann de Witte, heard him and said: "Father, what desperate words! If you merely want to die, let us then turn, sail in the midst of our enemies and fight ourselves to death!". This brave but foolish proposal brought the Admiral back to his senses, for he discovered that he was not so desperate and answered: "You don't know what you are talking about! If I did that, all would be lost. But if I can bring myself and these ships safely home, we'll finish the job later."

Then the wind, that had brought so much misfortune to the Dutch, saved them by turning to the west. They formed a line of battle and brought their fleet to safety through the Flemish shoals, Vice-Admiral Adriaen Banckert of the Zealandic fleet covering the retreat of all damaged ships with the operational vessels, the number of the latter slowly growing as it turned out that only very few ships had actually deserted in the night; most had merely drifted away, and now, one after the other, they rejoined the battle.

Aftermath

The battle was a clear English victory. Dutch casualties were initially thought to be enormous, estimated immediately after the battle of about 5,000 men, compared with 300 English killed; later, more precise information showed that only about 1,200 of them had been killed or seriously wounded. The Dutch only lost two ships: De Ruyter had been successful at saving almost the complete van, only Sneek and Tholen struck their flag. Tholen was the flagship of admiral Banckert who had moved his flag to another vessel. Both ships were burnt by the English.[5] The Dutch could quickly repair the damage. The twin disasters of the Great Plague of London and the Great Fire of London, combined with his financial mismanagement, left Charles II without the funds to continue the war. In fact, he had had only enough reserves for this one last battle.

While the Dutch fleet was undergoing repairs, Admiral Robert Holmes, aided by the Dutch traitor Laurens van Heemskerck, penetrated the Vlie estuary, burnt a fleet of 150 merchants (Holmes's Bonfire) and sacked the town of Ter Schelling (the present West-Terschelling) on the Frisian island of Terschelling. Fan-Fan was again present.

In the Republic, the defeat also had a far-reaching political effect. Tromp was the champion of the Orangist party; now that he was accused of severe negligence, the country split over this issue. To defend himself, Tromp let his brother-in-law, Johan Kievit, publish an account of his conduct. Shortly afterward, Kievit was discovered to have planned a coup, secretly negotiating a peace treaty with the English king. He fled to England and was condemned to death in absentia; Tromp's family was fined and he himself forbidden to serve in the fleet. In November 1669, a supporter of Tromp tried to stab De Ruyter in the entrance hall of his house. Only in 1672 would Tromp have his revenge, when Johan de Witt was murdered; some claim Tromp had had a hand in this. The new ruler, William III of Orange, succeeded, with great difficulty, in reconciling De Ruyter with Tromp in 1673.[6]

See also

Notes

- ^ also known as the St James' Day Fight, Battle of the North Foreland or Battle of Orfordness; In the Netherlands, the battle is known as the Two Days' Battle.

- ^ St James' day in the Julian calendar then in use in England

References

- ^ a b c Sweetman 1997, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d Palmer 1997, p. 138.

- ^ Brandt 1687.

- ^ Grant 2011, p. 132.

- ^ Scheffer 1966, p. 113.

- ^ Stewart 2009, p. 278.

Sources

- Brandt, Gerard (1687). Het Leven en bedryf van den Heere Michiel de Ruiter (in Dutch) (1st ed.). Uitgeverij van Wijnen, Franeker. ISBN 978-1-24639-809-0.

- Bruijn, Jaap R. (2011). The Dutch Navy of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-98649-735-3.

- Grant, R. G. (2011). Battle at Sea: 3000 Years of Naval Warfare. London: DK Publishing. ISBN 978-1-40535-335-9.

- Palmer, Mark (1997). "The 'Military Revolution' Afloat: The Era of the Anglo-Dutch Wars and the Transition to Modern Warfare at Sea". War in History. 4 (2): 123–149. doi:10.1177/096834459700400201. S2CID 159657621.

- Rideal, Rebecca (2016). 1666 : plague, war and hellfire. London: John Murray, publisher. ISBN 978-1-47362-355-2.

- Scheffer, Grant (1966). Roemruchte jaren van onze vloot. Baarn: Het Wereldvenster. OCLC 811870796.

- Stewart, William (2009). Admirals of the World: A Biographical Dictionary, 1500 to the Present. Jefferson: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-78648-288-7.

- Sweetman, Jack, ed. (1997). The Great Admirals: Command at Sea, 1587-1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-229-1.

10 Annotations

Second Reading

San Diego Sarah • Link

These notes come from https://threedecks.org/index.php?…, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sec… and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St.… .

Pepys seems to have had much anxiety about this battle, so I checked the Pepys encyclopedia and included some notes about what happened to people he knew who were involved.

In a naval battle the line contains three squadrons, each flying different colors. The lead squadron is called the van, the middle is called the center, and the end is brought up by the rear. Each ship has a Captain/Commander/Admiral, and the Generals-at-Sea control events as best they can by flying bunting from the mast of their flagships; each Squadron is overseen by an Admiral; but they do not issue orders about the sailing of the ships on which they stand as that is left to the Captains.

PRELUDE

In the winter of 1665-6, the Dutch created a strong anti-English alliance. On 26 January, Louis XIV declared war in accordance with a Treaty he could no longer ignore. In February, Frederick III of Denmark did the same after being paid a large sum. The promised English subsidies remained largely hypothetical, so Christoph Bernhard von Galen, Prince-Bishop of Münster made peace with the Republic in April at Cleves.

By the spring of 1666, the Dutch had rebuilt their fleet with much heavier ships — 30 of them possessing more cannon than any Dutch ship in early 1665 — and looked forward to being reinforced by a French fleet.

Charles II made a new peace offer in February, employing a French nobleman in Orange service, Henri Buat, as messenger. In it, Charles vaguely promised to moderate his demands if the Dutch would appoint his nephew, young William III in some responsible function and pay £200,000 in "indemnities".

Grand Pensionary De Witt considered the peace offer a bluff to create dissension amongst the Orangists and the Republican Dutch, and between the Dutch and the French.

A new confrontation was inevitable.

First came the Four Days' Battle in May, one of the longest naval engagements in history. A fleet of 80 ships, under Generals-at-Sea George Monck, Duke of Albemarle and Prince Rupert of the Rhine sailed, but early on Rupert was detached with 20 ships to intercept a French squadron which was thought to be passing through the English Channel, presumably to join the Dutch fleet. In fact, the French fleet was largely still in the Mediterranean.

With the return of the fresh squadron under Rupert the English now had more ships, yet the Dutch decided the battle on the fourth day, breaking the English line several times. When the English retreated, De Ruyter could not follow probably because of lack of gunpowder.

Both sides claimed victory: the English because Dutch Lieutenant Admiral Michiel de Ruyter retreated first, the Dutch because they had inflicted greater losses on the English, who lost ten ships against the Dutch four.

San Diego Sarah • Link

Both sides needed time to repair their fleets. The Dutch returned to the sea seven days before the English, partly because the English lacked manpower.

Capt. Richard Trevanian (who Pepys meets later on) was one of the skippers left in port. He was captain of the Marmaduke which lay either in the Thames or Medway for want of crewmen.

On 15 July, 1666 the Dutch fleet put to sea with troops aboard, intending to invade England, but again the French fleet did not show so the troops were landed back in the Netherlands.

The Dutch fleet of 88 men-of-war, 10 yachts and 20 fireships remained at sea, and on the evening of 22 July was to the north-east of the mouth of the Thames.

On 23 July, 1666 both fleets were becalmed. On the night of 23-24 a storm blew, doing damage to both sides.

During July 24 the Dutch kept the wind, and the English fleet of 89 warships maneuvered trying to obtain it. The night found the two fleets in the broad part of the Thames estuary between Orfordness and the North Foreland, the Dutch being to the N.E., and the wind blowing generally from the northward, but varying from N.N.E. to N.

Battle -- First day

As early as 2 A.M. on Wednesday, 25 July -- St. James's Day -- the Generals-at-Sea Rupert and Albemarle weighed anchored, and from then until about 10 A.M. the fleets slowly approached one another.

The English fleet of 89 ships seem to have been in line of battle close hauled or a point large on the port tack, Sir Thomas Allin's squadron leading. The Dutch fleet of 88 ships, in line of battle with the wind on the port quarter, or steering about six points large, Lieutenant-Admiral Johan Evertsen’s squadron leading; and, as they closed, the wind veered to N.W.

The Dutch line was ill-formed. Observers said it looked as if it bowed into a half moon: and, while the van and center were crowded, there was a gap between the center (under De Ruyter) and the rear (under Van Tromp).

The English line was as regular as a line of 5 or 6 miles can be. (The regularity of the English line during the Second Anglo-Dutch War often admiration, even by their critics.)

About 10 A.M., when the leading vessels of the two columns arrived within gunshot range, Allin [a tar] engaged Evertsen and the Dutch van, the squadrons holding parallel courses on the port tack, with the Dutch being to windward.

De Ruyter gave orders for a chase and the Dutch fleet pursued the English from the southeast in a leeward position, as the wind blew from the northwest.

Suddenly, the wind turned to the northeast.

Rupert then turned sharply east to regain the weather gauge.

De Ruyter followed, but the wind fell, and the Dutch fleet fell behind.

San Diego Sarah • Link

Evertsen’s van was becalmed and drifted away from the line of battle, splitting De Ruyter's fleet in two. This awkward situation lasted for hours.

Then a soft breeze began to blow from the northeast. Immediately, Allen’s van and part of the center formed a line of battle and engaged the Dutch van, still in disarray and basically defenseless.

The outnumbered Dutch failed to form a coherent line of battle in response, and ship after ship was mauled by the combined firepower of the English line. Vice-Admiral Rudolf Coenders was killed, and Lieutenant-Admiral Tjerk Hiddes de Vries had an arm and a leg shot off.

De Ruyter reformed the Dutch center and attempted to reach the van, but the wind was against him and he failed to reunite his forces. With the Dutch van defeated, the English converged to deliver the coup-de-grâce to De Ruyter's center.

Vice Admiral Sir Edward Teddiman of the White squadron furiously attacked the van of De Ruyter's fleet. The Royal Catherine was so roughly treated she was obliged to quit the line to refit.

Albemarle in the Sovereign, accompanying Rupert in the Royal Charles, predicted that De Ruyter would give two broadsides and run, but the latter put up a furious fight on the Dutch flagship De Zeven Provinciën. De Ruyter withstood a combined attack by the Sovereign and the Royal Charles, and forced Rupert to leave the damaged Royal Charles for the Royal James.

Capt. John Cox, captain of the Sovereign under Albemarle, a first rate of 100 guns, greatly contributed to the victory, which was later recognized by Rupert and Albemarle when he was knighted.

Capt. John Hubbard was captain of the Royal Charles, the ship on board which Rupert and Albemarle hoisted the standard. The conspicuous share born by this ship in the victory naturally is given to these two men. But while they were engaged in manœuvring the fleet, merit should be given to Capt. Hubbard, who, by his conduct and gallantry enabled them to devote their attention to the weightier part of their charge. It is said in the account published later by authority that "few ships need repairing except the Royal Charles, who bears honorable marks of that day's dangers."

The Dutch center's resistance enabled the seaworthy remnants of the van to make an escape to the south.

San Diego Sarah • Link

Meanwhile Capt. Jeremiah Smith with the English rear came up on Lieutenant-Adm. Cornelis Van Tromp, who put before the wind and broke through just ahead of the English rear, thus separating himself from his friends.

To De Ruyter, who later wrote bitterly to the States-General of Van Tromp's conduct, it appeared his subordinate allowed his squadron to fall far astern of its station, to be cut off by Smith. The evidence shows that, although Van Tromp was often headstrong, perverse and insubordinate, he never deliberately postponed action. He showed rashness rather than slothfulness or prudence.

The English van from the first asserted its superiority over the Dutch van.

Quickly the Dutch lost three flag-officers Jan Evertsen, Tjerck Hiddes de Vries, and Rudolf Coenders. It was overpowered, and by 1 P.M. was in flight eastward.

Van Tromp, commanding the Dutch rear, now brought his vessels to De Ruyter's rescue. Van Tromp ordered his vessels to the west crossing the line of the English rear under Smith.

From the moment Allin joined battle with Evertson (and went away in hot action with him), to the time when Van Tromp quit the Dutch line, two hours had elapsed.

It was then noon, and since 11 A.M. the wind had blown from the northward.

Van Tromp's rear squadron was the strongest of the Dutch, and Smith's rear Squadron was England’s weakest. If De Ruyter had understood Van Tromp's maneuver, it might have been defendable, but De Ruyter was mystified.

Van Tromp and Smith engaged in a confused melee, moving away on the starboard tack. The English rear was now cut off from the center, and Van Tromp's squadron began a dogged attack forcing Smith's ships to flee to the west. They became lost to sight in the direction of the English coast.

And the two vans and centers, broadside to broadside, headed nearly due east.

The pursuit of the English rear lasted well into the night, with Van Tromp destroying the Resolution with a fireship. Its captain, Willoughby Hannam [a tar] was 'A very stout able seaman' according to Coventry. He had served the Commonwealth and held 7 commissions after 1660. The Resolution ran aground and was burnt by a Dutch fireship.

Three times Van Tromp shot Smith's entire crew out of the rigging of his flagship, the Loyal London, before it caught fire and had to be towed home.

Edward Spragge [a tar] on the Victory was vice commander of the English rear, under Smith. Spragge felt so humiliated by these events that he became a personal enemy of Van Tromp, a feud which lasted until Spragge’s death. Worse, Spragge was later denounced as a coward in this action by his enemy, Robert Holmes -- but that’s a story for later.

Also aboard the Victory with Spragge was volunteer John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester. He again showed extraordinary courage at the height of battle, most notably rowing between vessels under heavy cannon fire, to deliver Spragge's messages around the squadron.

San Diego Sarah • Link

Capt. Charles O'Brien was appointed captain of the Advice, 48 guns, and served as one of the seconds to Sir Edward Spragge.

The English van from the first asserted its superiority over the Dutch van which fought magnificently. Quickly the Dutch lost three flag-officers Jan Evertsen, Tjerck Hiddes de Vries, and Rudolf Coenders; but it was overpowered, and by one o'clock was in full flight to the eastward.

Capt. Robert Mohun in the Dreadnought had a distinguished share in this second engagement.

Capt. Sir William Poole commanded the Mary of 58 guns.

Capt. Robert Robinson of the Warspight, a third rate of 64 guns, in which distinguished himself during the actions of 1666..

The English center had a more difficult and prolonged task before it, as De Ruyter and the captains under his immediate command fought stubbornly and gallantly.

Rupert had to shift his flag; the Royal Catherine and St. George had to haul out of action; and De Ruyter's flagship, the Zeven Provincien, was entirely dismasted after a savage conflict with Sir Robert Holmes in the Henry.

At 4 P.M. the Dutch center gave way; but both squadrons were in bad shape, and for some hours they drifted together to the southward, too mauled and exhausted to continue any kind of general action.

Capt. Charles Talbot’s ship was so disabled during the first day he had to put into Harwich. How this happened we do not know, but he appears to have had no further commands until 1678.

San Diego Sarah • Link

Towards night the English restarted the engagement. By then De Ruyter had re-formed his squadron, and, having stationed Vice-Admiral Adriaen Banckers, with 20 of the least damaged ships at the rear of his line, began a masterly retreat.

Before the retreat began, Banckers's first flagship, a vessel of 60 guns, and a ship called the Sneek ran Harlinyen, 50 guns, were abandoned and burnt.

In the meantime, the two rears had been closely engaged to the westward.

Dutch accounts have it that Smith continually gave way, and he did so in order to further separate the Dutch rear from the van and center. At first Van Tromp and Meppel (who was with him) had the best of the conflict. They burnt the Resolution, 64 guns; and, having gained the wind, they chased throughout the night of the 25th.

Capt. George Batts commanded the Unicorn, a third rate of 60 guns, was assigned to Richard Utber's division in the White Squadron. During the battle he had a falling out with Utber, and was dismissed from the service after the battle.

Rear Adm. Richard Utber [a tar] descended from a respected Lowestoft family and was married to Allin’s sister. Pepys mentions him three times, but not in relationship to this action. Pepys didn’t have cause to trust him either.

Captain Robert Clarke in command of the Triumph, a second rate, distinguished himself in this action.

Francis Digby, the second son of George, 2nd Earl of Bristol, was in command of the fourth rate frigate Jersey. His bravery is indicated by the fact that when the Jersey went in for repair during the fight, Capt. Digby asked permission to go back to sea on another ship as a volunteer (a request rejected by Albemarle).

San Diego Sarah • Link

Second day

The main battle continued in a desultory way during the night, and became brisk again on the morning of the 26th. The wind was now strong from the N.E., and the Wielings shallows were close at hand, so the pursuit of the Dutch van and center finally had to be discontinued.

Meanwhile, many miles away, Van Tromp broke off pursuit of Allin, well-pleased with his first real victory as a squadron commander.

During the night, a ship brought him the message that De Ruyter had been victorious, so Van Tromp woke up feeling happy and satisfied.

All that abruptly changed when his squadron discovered the drifting flagship of the dying Tjerk Hiddes de Vries and learned his colleagues had suffered defeat, and that part of them had taken refuge in the Wielings.

Suddenly Van Tromp feared his ship was the only fighting remnant of the Dutch fleet, and he was in mortal peril. Behind him, the ships of the English rear which were still operational had turned to the east. Smith had the wind once more, and was in chase.

In front, the other English squadrons surely awaited him.

On the horizon, only English flags could be seen.

Smith chased Van Tromp all day.

Maneuvering wildly, Van Tromp began to drink gin to restore his nerve. He dodged all attempts to trap him.

In the evening, Albemarle and Rupert, far to leeward and unable to interfere, could see Van Tromp flying for Flushing, with Smith at his heels.

When Van Tromp reached Flushing, to his great relief he found the rest of the Dutch fleet.

At 11 P.M. on the 26th the English van and center anchored off the Dutch coast.

When Smith’s squadron rejoined the fleet, he reported Van Tromp had escaped with a shattered force.

In port, it took Van Tromp six hours to gather enough courage to face De Ruyter. It was obvious to him that he never should have allowed himself to be separated from the main force.

De Ruyter hadn't mentally recovered from the events of the previous day, so he immediately blamed Van Tromp for the defeat and ordered him and his subcommanders, Isaac Sweers and Willem van der Zaan, from his sight and told them to never again set foot on his flagship.

San Diego Sarah • Link

When the sun rose, De Ruyter discovered his position was hopeless. Adm. Evertsen had died after losing a leg. His force was reduced to about 40 ships, most of which were inoperable, and they were crowded into a small harbor. His 15 good ships were missing, presumably having deserted during the night.

A strong gale from the east prevented a retreat to the Republic, and to the west the British van and center (about 50 ships) surrounded Flushing in a half-circle, safely bombarding his fleet from a leeward position.

De Ruyter became desperate. When his second-in-command of the center, Lieutenant-Admiral Aert Jansse van Nes visited him for a council of war, he exclaimed: "With seven or eight against the mass!" He then mumbling: "What's wrong with us? I wish I were dead." His close friend, Van Nes, tried to cheer him up, joking: "Me too. But you never die when you want to!"

No sooner had the men left the cabin than the table where they had been sitting was smashed by a cannonball.

However, the English also had problems. The gale prevented them from closing with the Dutch. They tried to use fire ships, but they had trouble reaching the enemy in harbor. Only the sloop Fan-Fan (Rupert's personal pleasure yacht) rowed to the Dutch flagship De Zeven Provinciën to harass it with its two little guns, much to the amusement of the English crews.

The flagship warded off another attack by a fire ship, the Land of Promise. Van Tromp didn't report for a briefing. De Ruyter’s anxiety became unbearable. He purposely exposed himself on deck.

But the English seamen failed to hit him, and De Ruyter was heard to say: "Oh, God, how unfortunate I am! Amongst so many thousands of cannonballs, is there not one that would take me?"

His son-in-law, Captain of the Marines Johann de Witte, overheard him and said: "Father, what desperate words! If you merely want to die, let us then turn, sail in the midst of our enemies and fight ourselves to death!"

This brave but foolish proposal brought De Ruyter to his senses. He answered: "You don't know what you are talking about! If I did that, all would be lost. But if I can bring myself and these ships safely home, we'll finish the job later."

Then the wind saved the Dutch by turning to the west. They formed a line of battle and took their fleet to safety through the Flemish shoals, Vice- Admiral Adriaen Banckert of the Zealandic fleet covering the retreat of all damaged ships with the operational vessels. The number of operational vessels slowly grew as only a few ships had really deserted in the night; most had drifted away, and now rejoined the battle line.

San Diego Sarah • Link

The St. James Day battle was an English victory. No greater tribute can be given on the performance of England’s admirals and commanders than to say they had the honor of defeating three great seamen: De Ruyter, Evertzen, and Van Tromp.

Dutch casualties were said to be enormous, estimated immediately after the battle of about 5,000 men, compared with 300 English killed. (Later, a better count revealed that only about 1,200 of the Dutch had been killed or seriously wounded.) The Dutch lost the four Flag-officers already mentioned, and numerous captains, including Euth Maximiliaan, Hendrik Vroorn, Cornelis van Hogenhoeck, Hugo van Nijhoff, and Jurriaan Poel.

The “victors” only lost the Resolution, two or three fireships, and a relatively small number of men. No flag-officers fell, and the only captains who lost their lives were Hugh Seymour of the Foresight, John Parker of the Yarmouth, Joseph Sanders of the Breda, Arthur Ashby of the Guinea, and William Martin of the hired East Indiaman London.

Capt. Joseph Sanders of the Breda, 48 guns, was wounded in the leg by a musket shot which was initially thought trivial, but he unhappily died a few days later.

Survival was enough for the Dutch, as the English could not afford to replace their losses.

In the Republic the “defeat” had far-reaching political fallout.

Van Tromp may have defeated Allin, but was accused by De Ruyter of being responsible for the plight of the main body of the Dutch fleet by chasing the English rear squadron as far as the English coast. To defend himself, Van Tromp let his brother-in-law, Johan Kievit, publish an account of his conduct.

As Van Tromp was the champion of the Orange party, the conflict led to much party strife. Van Tromp was fired by the States of Holland on August 13.

Five days later Charles II made another peace offer to Grand Pensionary De Witt, again using Henri Buat as an intermediary. Among the letters given to De Witt was one included by mistake which contained the secret English instructions to their contacts in the Orange party, outlining plans for an overthrow of the States regime.

Henri Buat was arrested. His accomplices fled to England, among them Johan Kievit who was condemned to death in absentia. Van Tromp's family was fined, and he was forbidden to serve in the fleet.

De Witt now had proof of the collaborationist nature of the Orange movement; the major city regents distanced themselves from its cause. Buat was condemned for treason and beheaded.

The mood in the Republic now became very belligerent.

In November 1669, a supporter of Van Tromp tried to stab De Ruyter in the entrance hall of his house.

In 1672 Van Tromp had his revenge when Johan de Witt was murdered (some alleged Van Tromp had a hand in this).

In 1673 the new ruler, William III of Orange, succeeded in reconciling De Ruyter with Van Tromp.

San Diego Sarah • Link

The English had fallout from this action as well.

Sir Robert Holmes’ rivals Sir Jeremiah Smith (admiral of the blue) and Sir Edward Spragge (vice-admiral of the blue) had been promoted above him.

Holmes used their conduct during the St. James' Day Fight, to start a bitter quarrel with Smith which led to them fighting a duel.

The recriminations between the officers and their respective factions played a role in the subsequent Parliamentary investigation over embezzlement in the naval administration and the conduct of the war.

###

For a list of participating vessels on both sides, and the names of their commanders, see: https://threedecks.org/index.php?…

###

Since who was a "tar" and who was a "gentleman" played a decisive role in this battle, I would love to find a list. I've looked in all my books but haven't found anything helpful.

###

For fun reading about these times I recommend "The Blast that Tears the Skies" (1665) and "Death's Bright Angel" (1666) both out in paperback by J.D. Davies.